April 2023 - Looks a lot like 1997 all over again

by Stephen Bennie 2023-04-05

Let’s jump back in time to 1997 when the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) was just about to make a horrible policy error.

The fall out from the error saw the RBNZ abandon its use of the Monetary Conditions Index (MCI) for determining interest rate settings, and the sorry episode became the topic of case studies in prestigious American universities.

At that time Dr Donald Brash was the Governor of the RBNZ and had been since 1988. In 1997 he introduced a new tool to help guide monetary policy, the MCI. The MCI was calculated using a ratio of interest rates and currency levels, and its introduction was seen as a global revolution in managing interest rate settings. Not everyone was convinced but Brash was a devout convert. Here is an extract from his December 1997 Monetary Policy Statement.

Extract from RBNZ’s December 1997 Monetary Policy Statement

First, despite some doubts which have been expressed about the way in which our Monetary Conditions Index is working, we are entirely happy with it. We are no more confident now than we were a year ago that we know with any degree of precision the comparative influence of interest rates and the exchange rate on medium-term inflation. Nor are we any more confident about the stability of that ratio over time. Clearly, our `two-for-one' assumption is subject to very considerable uncertainty. That is why, even in the immediate aftermath of a new projection, we do not force monetary conditions to conform exactly with `desired'. But the MCI reminds everybody that, in a small open economy, both interest rates and the exchange rate form important parts of the monetary policy transmission mechanism, and gives markets some guide to how we weight the relative importance of those channels. It is especially useful in helping public understanding when, as often in the last 12 months and more, interest rates and the exchange rate are moving in opposite directions. While few other central banks use such an index in a formal sense at this time, it is clear that all central banks, even the Federal Reserve Board in the US, have to take exchange rate effects on inflation into account in determining the appropriate stance of monetary policy.

Source: RBNZ

It is telling that some doubts were noted in the extract above because within two years of the above statement, the MCI was abandoned. Or as the RBNZ later put it – “The MCI was a branch that we lopped off fairly quickly”. What had gone so wrong, so quickly?

As a direct result of its fixation with the MCI the RBNZ had been raising cash rates during 1997. However, in July 1997 Thailand devalued its currency relative to the US dollar, which triggered similar responses in Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia. South Korea was on the verge of defaulting on its sovereign debt. Access to capital in the region was suddenly scarce as global investors pulled back. What became known as the Asian Financial Crisis resulted in most countries in the region facing deep recessions. And the effects were also felt in New Zealand, which would ultimately enter its own recession. There can be little doubt that the recession experienced by New Zealand was exacerbated by the rate rises the RBNZ did in 1997 because of the MCI, even in the face of a financial crisis in the region. It was a Brash bungle rooted in the failure to properly consider factors other than the MCI.

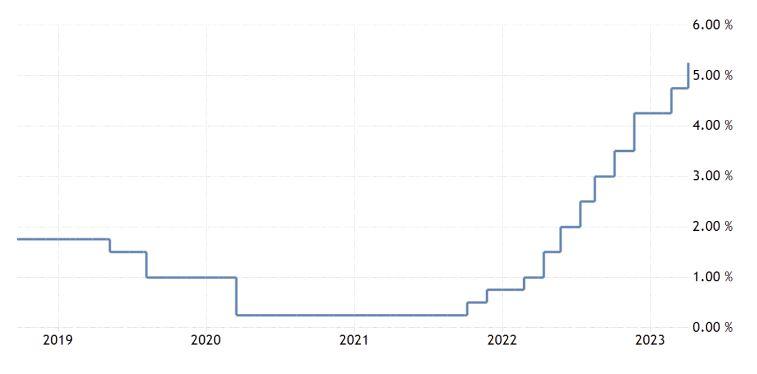

Jump forward to the current day and it feels like a very similar scenario could be playing out in front of our eyes. The RBNZ has raised the official cash rate yet again by 0.50% to 5.25%. This was a surprising move as the market had expected 0.25% or perhaps even a pause. However, due to the most recent Consumer Price Index (CPI) number still running well above target the RBNZ kept up the aggressive pace of rate rises. It is true that our CPI is high and needs to come down, but there are increasing signs that demand in our economy is fast ebbing out. It should also be remembered that there is a time lag between interest rate changes and its eventual impact on the economy. Just basing the decision to rise on the level of the CPI has unfortunate echoes of the RBNZ raising interest rates in 1997 just because that is what the MCI was saying they should do.

We have seen offshore that raising interest rates aggressively, as most central banks have done during 2022 and earlier this year, can break things. The best examples so far have been the collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse. Meanwhile evidence of stalling demand in the New Zealand economy is fast piling up. In recent weeks The Warehouse reported a large downgrade due to weaker consumer demand. Large Auckland based construction business, Scarbro Construction, just went into receivership. Retirement village operator, Summerset Group, just downgraded earnings guidance as unit sales have weakened in recent weeks. Meanwhile many New Zealand households are experiencing significant stress as they refinance their mortgage at a considerably higher interest rate. Anecdotally there appears to be many New Zealanders that are being forced to borrow from their retired parents in an effort to keep their homes. There is a real risk that this latest 0.50% OCR hike is the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

Share article:

Other Insights

Stay updated with Castle Point Funds.

Investments

Resources

Company

Castle Point Funds

Perpetual Guardian Tower

Level 23, 191 Queen Street

Auckland 1010

PO Box 105889

Auckland 1143, New Zealand

E info@castlepointfunds.com

PG Funds Limited is the issuer and manager of the Castle Point Funds Scheme.

2025 Castle Point Funds, Inc. All rights reserved.

Privacy Policy